Editor’s note: The earliest version of this story did not explain the difference between the budget “reserve” and a budget “surplus.” A sharp-eyed reader caught the error, and we have added a parenthetical explanation below. Thanks to our vigilant readers for the help, always.

At Merced College, the trouble with Higher One began during the second week of the fall semester. That’s when the College administration learned many students would not be receiving their financial aid when promised.

Because it was Higher One’s first attempt to fulfill its contract to distribute financial aid, many in the College’s upper echelon were not happy. Vice President of Instruction Dr. Kevin Kistler issued a tersely worded email informing College personnel of the situation:

“Higher One changed its policy and told us yesterday, that they will withhold student access to financial aid until they had finished the student I.D. verification process. Their new policy contradicts their previous practices and promises made to us…Through no fault of anyone on this campus, some of our students will suffer in terms of class progress and learning.”

Kistler asked faculty members to “consider the students’ plight and help them if you can.”

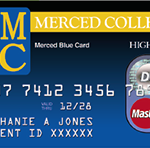

For most Merced College faculty, Kistler’s letter was the first they knew about a change in the disbursement of financial aid. Previously, students picked up checks on campus. Now, they were issued a Higher One, “blue card,” which was in theory to be used like a debit card.

Immediately on hearing about the students’ problems, English Professor Jory Taber began a quick investigation into Higher One. He soon learned that as recently as 2012, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) had ordered Higher One to pay $11 million to over 60,000 students as restitution for, “deceptive and unfair fee practices.”

Taber erupted. He dashed off a quick email to a few English colleagues and cc’d Dr. Kistler as well:

“I love that Merced College has chosen to use Higher One debit cards to disperse financial aid monies. In these trying economic times where our budget is down to a scary 14% surplus, it only makes sense to shift the burden of our alleged woes onto the backs of our most abundant resource. In fact, to add a bit more clarity to this promising metaphor, we should all begin to think of our student population along the lines of pack animals, or “some inert exploitable substance” rather than falling back on old fashioned mission statements or unsustainable principals of morality.”

Like many at Merced College, Taber was especially disturbed that the administration had chosen a cost-cutting measure that transferred some of the costs to needy students when the College had a budget reserve far in excess of state recommendations. (Though Taber used the phrase “budget surplus” in his email, the was referring to the reserve, which is actually an emergency set-aside fund. Like most community colleges in recent years, Merced College has actually been operating at a budget shortfall, which the reserve has helped cover.)

In effect, Merced College, like over 500 other colleges and universities in the United States, had outsourced what it sees as a burdensome administrative chore to Higher One.

The brainchild of three Yale undergraduates, Higher One offers colleges and universities too good a deal to refuse. In essence, Higher One assumes the expense of distributing financial aid at a fraction of the cost the school pays. Higher One is eager to take on the distribution costs because it makes most of its money by charging fees for the use of its debit cards.

Most likely as a result of its recent troubles with the FDIC, Higher One now offers scrupulously detailed explanations of how students can use the card to avoid unnecessary fees.

Nonetheless, some faculty members at Merced College think the explanations are misleading. The “blue card” clearly reads, “debit card.” But in order to avoid a fee, students are advised to “always choose credit” at the checkout. Given the rush during the early weeks in the semester, many faculty members believe the cards will confuse busy students.

Because it makes most of its profits from fees, Higher One is betting that even when ostensibly given a choice, students will select the “pay” option, perhaps unwittingly.

For Merced College Philosophy Professor Keith Law, this amounts to both the College and Higher One betting against students. When Law learned about the Higher One contract, he assigned students in his Critical Thinking classes a set of tasks that include investigating Higher One’s relationship with Merced College.

Law is especially interested in how the College has handled the savings accrued from outsourcing financial aid disbursements. He’s also not happy about transferring money outside a very poor region into the ever deeper pockets of yet another of our ethically tainted corporations.

Given his long history as a regional gadfly, Law’s project of consciousness-raising may change the odds in the Higher One game dramatically. It’s even possible that Higher One’s and Merced College’s bets against the students will be the rare occasion when the students emerge victors, even against corporate and institutional powers.