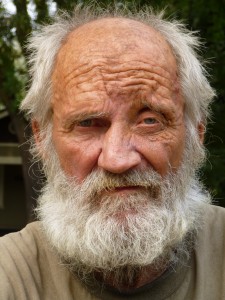

When Carl Wolden hit the streets of Modesto late in 2004, he was embittered and angry. He had never gotten over the injustice of paying child support to a woman who used much of the money for hard drugs.

After making $31 an hour in his job at a major auto parts firm in San Francisco and making decent money in the Alameda shipyards, he found it increasingly difficult to make ends meet as his income fell in Modesto. As the back log of child support payments grew, he realized he would never catch up. He finally gave up hope.

For a short while, Carl hung around Graceada Park, where he had lived in his car until it was towed. While there, he befriended a young woman who almost daily came to the park with her children.

Louise was clearly troubled, and Carl found himself attracted to her. He enjoyed playing with her children, and was desolated when she and her husband moved to Oregon. At that point, Carl decided to head for Moose Park, where many of the homeless he had known from the Modesto Gospel Mission had set up camps.

Moose Park was at that time a nexus for homeless drug use and distribution. Carl soon found that his natural business sense and ability to interact with people were strong assets for “doing business,” the euphemism for selling drugs.

Though he had always hated heroin and cocaine, Carl felt marijuana had been unfairly demonized as a gateway drug. He also noted that many of the homeless used methamphetamine but were somehow able to manage their habits even while maintaining long and difficult routes gathering bottles and cans.

Carl soon became known to an older group of homeless people as a reliable source for these drugs. He was so fair in his dealings that some homeless men gave him their money to manage, and Carl made sure they always had enough for the necessities many drug users neglected. He also made it a principle never to sell young people who were living with their parents. He thought getting them started on drugs was predatory and dishonorable.

At that time many of the homeless were fed by volunteers at Tower Park in downtown Modesto. One day Carl was surprised to find Louise there. She had left her husband and children in Oregon and was now homeless and attached to a “canner” named Frank, a Native American and workaholic collector of recyclable bottles and cans.

Carl and Louise renewed their friendship. One day they were sitting on the grass in Tower Park having lunch when Carl inadvertently left his backpack open, exposing a large bag of marijuana. Before anyone knew what was happening, Carl received a vicious running kick in the head from one of the local heroin addicts.

Woozy, he tried to struggle to his knees, but another brutal kick knocked him out and fractured his jaw. The assailant then took Carl’s bag of marijuana and sauntered away.

Stunned, Louise managed to get someone to call an ambulance. At the hospital, Carl received a cursory examination and was released. When he returned to Moose Park, he was surprised to find his attacker there, apparently welcomed by all who had witnessed or heard about the attack.

For weeks Louise and Frank made sure Carl had soup and liquid sustenance. But none of the three could accept the general indifference to Carl’s assault. Though they themselves were drug users, they had never allowed their habits to reduce them to theft or savagery.

“We formed a pact,” says Carl. “We agreed we’d never again let one of us be attacked without the others jumping in to help. Then we left Moose Park.”

Louise began referring to the group as “family.” When they started spending the days in a park near central Modesto, word got out that anyone who abused one of the three abused all of the three and would face swift retaliation.

“We made a few simple rules,” says Carl. “The most basic rule is, ‘no stealing.’ No stealing of any kind, not from the homeless, not from the public, and not from nearby homeowners. It doesn’t make sense to make enemies of the people around you.”

Carl also made it a point to discourage heroin and cocaine users from frequenting the park. He felt they would do anything when needing a fix, and didn’t want to see his environment become lawless and unsafe. His own drug use diminished dramatically once he found a safe haven.

Under Frank’s tutelage, Carl soon learned he could make as much as $25 a day collecting bottles and cans. The income was almost as much as he could have made at low-paying jobs after his child-support payments were deducted.

While there were a few initial encounters with predators and bullies, people soon learned that Carl, Louise and Frank were a formidable trio. All had suffered routine beatings as children and were unafraid of physical harm.

Louise was especially fierce. Word spread throughout the homeless community after she brought a large bully to his knees with a swift and powerful punch to the solar plexus. And though Frank was most often taciturn and occupied with his huge piles of bottles and cans, it was easy to imagine him applying his relentless energy in a berserker defense of his only friends.

Carl also made it a principle to come to the defense of those he called, “little ones and least ones.”

“They all know, they all know because I tell ‘em,” says Carl. “They bother the least one, the little one, they’ve got me. I don’t care if there’s five of ‘em, they’ve got me and I’m wiry and I keep comin’. Don’t bother the least ones or the little ones or the ones that need help.”

In Carl’s mind, the “little ones” are people easily bullied, most often because they’re small or weak. The “least ones” are the damaged, and it doesn’t matter to Carl where the damage has come from. Drug users ravaged to the point of starvation, the mentally ill, or those recently on the streets find themselves watched over when they wander into the park where Carl and his friends have established “The Family.”

Lately, a homeless man known as “Rewind” for his habit of walking backwards has found refuge near Carl and his friends. When people see him on his back in an apparent stupor, Louise assures them he’s okay.

“He’s family,” she says. “He don’t hurt nothin’ or nobody but himself. We’re watching out for him.”

When Louise and the rest have food, they make sure Rewind is invited, and if anyone else in need is around, they’re invited to partake. Lately, that includes “Jackie,” a skeletal wraith ravaged by crack cocaine.

Despite the daily struggle for food and shelter, Carl and family have somehow managed to establish practices of kindred charity with those even needier than they are—a spiritual commitment that animates their precarious existence with unacknowledged gestures of grace.

Next: Faces of the Homeless: Carl, Part IV

As with all of your articles in this series; VERY well written, informative and interesting.

Thank you Shirley. I’m learning a lot from the people on the streets.

Eric:

What a poignant, moving story.