With a profile that could easily have served as the “heads” side of an American coin honoring its native residents, Edward “White Horse” Mendez was a legendary presence among the small circle of homeless people who lived in and frequented Modesto’s Beard Brook Park. He died Wednesday, March 10. He was sixty-eight years old.

With a profile that could easily have served as the “heads” side of an American coin honoring its native residents, Edward “White Horse” Mendez was a legendary presence among the small circle of homeless people who lived in and frequented Modesto’s Beard Brook Park. He died Wednesday, March 10. He was sixty-eight years old.

“White Horse taught me how to survive out here,” said one man several decades his junior.

“He took me under his wing and helped me get out,” said another, who had managed to escape homelessness.

Born in San Francisco, White Horse claimed to have played drums for Carlos Santana and a long list of other Bay Area musical luminaries. He’d also had a stint as a street artist.

“I started living on the streets when I was seven,” he said when asked how long he’d been homeless. “Whenever the cops found me and brought me home, my parents always told them to keep me. They said they didn’t want me.”

Like many homeless people, White Horse began using drugs at an early age, hardly into his teens.

“I stayed up for 28 straight days one time,” he said, when describing his days using methamphetamine. “They used to take me to the hospital with needles sticking out of me.”

Some time in the 1990s, White Horse moved to Sonora, where he became part of a small local homeless population. By then, his drug use consisted almost entirely of alcohol and marijuana.

In 2002, he was convicted of voluntary manslaughter for alleged participation in the gory murder of an alcoholic Sonora man who frequently invited homeless friends to his apartment for extended drinking bouts. White Horse always claimed that he hadn’t been present during the murder; nonetheless, he ended up serving eleven years hard time.

He landed in Modesto because, “They dumped me here when I was released. They gave me $200 gate money and dumped me near the jail. Where was I supposed to go?”

After failed attempts to make it through programs offered by the Modesto Gospel Mission, White Horse established residence under a large oak on the hillside near the entrance to Beard Brook Park. With no income other than food stamps, he subsisted on a regimen of beer and marijuana, supplemented by meals served by the church and volunteer groups who visited the park regularly. Most of the time, he spent his nights under the stars. In bad weather, he used a blue tarp. He occasionally had use of a donated tent.

Stoic and unperturbed by the tickets he received for unpermitted camping, White Horse had a simple routine for dealing with law enforcement. During periodic sweeps when homeless people were ordered to leave the park, he packed his small bundle of belongings onto a hand truck and wheeled it to a new location, usually no more than half a mile away. After a short wait, oftentimes only a few days, he’d move back under the oak tree.

During bad winter weather, White Horse would turn himself in and serve time for his long list of tickets and warrants.

Like many people who had spent long years in prison, White Horse was well read in his favorite genres. His taste ran to the lurid and cartoonish fiction of the past, including a particular fascination with the “Tarzan” and “Doc Savage” series. His dog was named “Greystoke,” after Tarzan’s given name. He knew in specific detail the history of comics and admired the great cartoonists, including the Marvel stable.

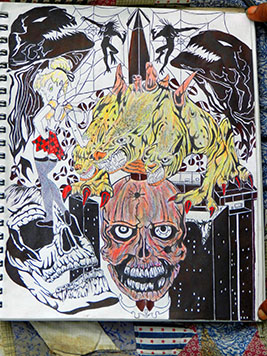

White Horse spent much of his time drawing and produced a large portfolio of “prison art,” an extravagant and fantastic genre he represented with meticulous detail.

When he began receiving SSI income, White Horse gained entry into one of Modesto’s low-income housing programs, but he was never comfortable indoors. When he moved in, he seriously considered setting up a tent inside, just to feel more at home.

“It’s like prison with a key,” he said, not long before being evicted for smoking in his room.

Always a person who kept to himself, White Horse nonetheless did well when Beard Brook Park filled with residents after local authorities permitted camping there following a court decision that prohibited punishing homeless people for sleeping on public property.

A strict observer of the unwritten codes of homelessness and a believer in “park justice,” White Horse was widely respected for his stoic self-sufficiency. He had a small circle of close friends who enjoyed his stories, unique wit, and advice.

A very small man whose weight never topped 120 pounds, he was seldom bullied and never intimidated. Once when a large man barely out of his teens was menacing people with a heavy chain, White Horse yelled, “Stop that,” and it stopped.

Asked why the man had obeyed, White Horse only said, “He’s lucky I didn’t take his scalp and all his horses.”

Not long after Modesto’s homeless people were moved from Beard Brook Park to the Modesto Outdoor Emergency Shelter (MOES), White Horse was diagnosed with cancer of the liver. From that time onward, he was often found walking slowly down McHenry Avenue, after one of many hospital stays.

When MOES closed, he began a labyrinthine journey from Stanislaus County’s low-barrier shelter to various motel rooms. Sometimes he couldn’t be found. Near the very end, a small circle of friends managed to get him into hospice care, where he spent his last days.

Few noted his passing, but those who did felt fortunate to have known him. He expected nothing and often received less, but he never lost his dignity. He didn’t whine, and he didn’t beg. Like many who have gone before him, he’ll be described as a “vagrant,” or “transient,” or “bum.” He was more than that; he was a human being. He stood against the storm as best he could, and better than many.

Eric, this is one of the best tributes to anyone I have ever read in my entire life. It will be shared widely and I hope everyone who reads this will give a donation to The Valley Citizen, in honor and to help continue this type of journalism.

Thank you Christine, and thank you for the donation. People wishing to donate should use the “Donate” button and PayPal.

White Horse as most knew him, with a spirit close to nature, a love for the outdoors and living in a tent, was at peace. But that peace was unfortunately denied him as our society has demands achievable or not to be housed, or is it really that we want those free spirits out of sight I ponder? May you now rest in forever peace my friend.

Whitehorse lived life on his terms and never asked for much. He always exchanged kindness for kindness and respect for respect. The world has lost a warrior and he will be greatly missed by those who were blessed to know him.

Another one of us gone

My beautiful friend, I never imagined seeing your face in my smartphone. You are, and will be, cherished.