Angela Morales was hired to teach English at Merced College in 1997. A graduate of the prestigious Iowa Writing Program, Morales proved to be a gifted teacher and valued associate. Few could have guessed, however, that their quiet and unassuming colleague would prove to be the writer extraordinaire she became a few years later.*

Angela Morales was hired to teach English at Merced College in 1997. A graduate of the prestigious Iowa Writing Program, Morales proved to be a gifted teacher and valued associate. Few could have guessed, however, that their quiet and unassuming colleague would prove to be the writer extraordinaire she became a few years later.*

A hint of things to come arrived when one of Morales’s essays was featured in The Best American Essays of 2013. “The Girls in My Town” presents a piercing look at teen motherhood in our own Valley town of Merced. It’s a brilliant dissection of the poverty, pop culture, and misaligned social services that help define a region widely known as “The Appalachia of the West.” Here’s an excerpt, about a young girl from a family Morales calls, “The Meth Joads”:

The girl, Misty Joad—no more than sixteen and heavily pregnant—paces the sidewalk and talks languidly on the phone like she’s waiting for someone to pick her up and take her somewhere. Every few days a red-faced teenage boy shows up and the two of them drive away in his Mustang. Then the boy stops coming. Eventually Misty Joad walks the sidewalk with her newborn baby. But imagine her power. Even with dirty bare feet and no plans, her body has declared a coup: “If you won’t love me, here’s a person who will.”

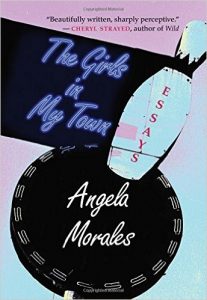

Brilliant as it is, “The Girls in My Town” might not be Morales’s best work. That became evident when The University of New Mexico Press published an anthology of Morales’s essays earlier this year.

Named after the featured essay, The Girls in My Town includes twelve masterpieces of the essay form. It won the River Teeth Nonfiction Book Prize over 270 other submitted manuscripts, and even such an honor can’t begin to signify just how fine a collection this really is.

Reading Angela Morales is like watching an acrobat with moves you’ve never seen—what will she do next? Who else could make an obsession with bowling into a fascinating essay into adolescence (“Chief Little Feather, Where Are You?”)?

Her subjects are all familiar—pets, death in the family, marital discord, troubled students—but her illumination of those subjects is magical. “Walking upright takes its toll,” writes Morales, but it’s a toll she bears with unusual grace, paying not only her own way but offering dividends of insight and inspiration for the rest of us.

One passage she’s the sly kid with answers to questions most of us don’t dare ask, the next she’s a conjurer of light in dark places we don’t dare look. A master of macabre humor and mordant wit, she’s also a genius at delivering us from what the late David Foster Wallace called today’s curse of irony.

In, “An Elegy (and Apology) to Dogs I’ve Loved,” Morales captures exactly that combination of devotion, guilt (for not loving more and better), and longing that marks the loss of a childhood pet:

My darling Tiger, I am learning about the folly of men. I am stroking your nose, watching you squint against the sun, and I want to keep you here forever, gentle Tiger. Some men do not believe in the souls of animals, perhaps because they do not believe in the souls of themselves. I am sorry that I did not stop him, that bricklayer man working in our backyard who wanted to amuse me by hurling you into the sky, who laughed his head off as he flung you up and then barely caught you as you sailed into his rough, brown hands. I still see his cement-streaked face and your reflection in his sunglasses—your legs askew, eyes bulging with terror. I am sorry my tongue froze that day. Since then I have learned to speak up, and I think you would be proud (if dogs can be proud). I once saw a man pounding his dog with his fist and I told him, “How about punching someone your own size, you loser?” and he said, “Shut up, bitch, before I punch you,” and I said, Oh, please do, be my guest.”

Morales’s elegies to her dogs—Taco, Max, Petunia, and all the others—poignant as they are, mark only a small fraction of her broad emotional landscape. She finds telling significance in small details (an infant’s headband, ammonia-scented hallways, the creases across a rat’s paws) and in quotidian routines of experience, shining the light of courage and comprehension in ordinary places with extrasensory perception.

Anyone who’s ever tried to teach anything to a troubled young person must read “Bloodyfeathers, RIP.” A memorial, a foray into writing as existential inquiry, and a candid portrayal of teaching’s often harsh demands, “Bloodyfeathers RIP” poses the ultimate writer’s question:

Do we assign too much significance to these lives that randomly crisscross ours, or not enough?

In the case of Angela Morales, the answer to her question is “neither.” She assigns just enough significance to leave us wanting more, much more.

*Morales now teaches at Glendale Community College in Pasadena.

*I knew.

I rue.